Last autumn, I posted a blog that explored the implications of the revised curriculum, and the revised SATs, for reading at primary. Since then, I have facilitated 3 professional development groups in Hampshire, at Hordle National Support School, the Aspire Teaching School Alliance at Overton Primary and the ETC Teaching School Alliance at Wildern School.

Our brand, Blended Reading for Mastery, has been gathering momentum with the schools involved as they have begun to understand key principles and adapt practice.

Blended? Reading provision takes in to account the blend of texts, the blend of contexts, the blend of skills and the blend of approaches when teaching reading comprehension.

Mastery? Our goal is to teach all concepts and skills to all children – so if the objective doesn’t change, we adapt approaches to enable access.

Since I will be presenting on BR4M at Pedagoo Hampshire 2017 on Saturday 16th September, and new courses will be advertised to start later in the autumn, this seems an apposite time to reflect and take stock. Last autumn’s blog focused on what and how I thought provision might need to change. This blog takes stock of the evaluation evidence that has emerged from working with the three PD groups:

- What aspects of reading provision have schools begun to change? What would visitors, senior leaders, Ofsted inspectors observe in these schools?

- How do the schools know that reading confidence and competence is improving?

1. What has changed?

- All children have access to challenging, literary texts at the core of the curriculum. This means not just a read-aloud at the end of the day, but inspiring texts as a focus for interpretation and writing stimulation as an English entitlement.

- Most teachers are achieving this by teaching reading in whole class contexts as part of blended Small group and whole class contexts are designed to be linked and complementary.

- For this to work, teachers’ planning deliberately scaffolds access to challenging texts. Faced with a new text, good readers naturally make connections with their existing vocabulary store and language patterns, their knowledge of texts, their experience and knowledge of the world, in order to build meaning: build the movie in their head. The reading teacher structures and enables this internal process to make it an external and collaborative meaning making process.

- The curriculum architecture makes connections between texts. Bob Cox’s books, Opening Doors to classic poetry and prose, refer to these as link texts. On the BR4M course, teachers have taken a journey through Anthony Brown’s The Tunnel, or Aaron Becker’s wordless picture book, Journey – as examples of portal stories – before bridging to The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. Starting with a short, though still complex picture book text, readers can reason deeply about the portal as a narrative device – What did the journey to another world reveal about the characters? Did they change? What caused them to change? Did their everyday world seem different to them when they returned? What, indeed, caused them to go through that portal in the first place? Part of developing mastery as a reader is carrying an understanding of common story shapes – narrative patterns – with you to support meaning making. That ‘understanding’ at best is not a concrete recall. It opens the possibility to make links, and see patterns – a key aspect of mastery learning. One year 6 teacher planned a journey from Nick Butterworth’s The Whisperer to Romeo and Juliet. A year 3 teacher explored the short ballad The Grateful Dragon by Raymond Wilson before exploring Ted Hughes’ The Iron Man. Both stories begin as ‘community under siege’ stories but become healing allegories. We are building a bank of these linked tapestries of texts that build the big shapes of stories and deeper, more critical thinking about why they might be written and how they work.

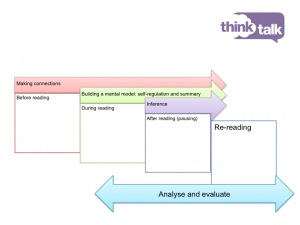

- Journeys through texts are slower and deeper. Good readers self-regulate. They notice when meaning breaks down, when stories are puzzling or take an unexpected turn. Break-down and repair, questioning, predicting, returning to interpretations and revising them in the light of new evidence happen openly, outwardly, collaboratively to grow the reading brain. There is significant research evidence that metacognition strategies are central to higher order thinking and key to improving the attainment of our most vulnerable learners. Revisiting our thinking takes time, practice and deliberate effort.

- More time is spent on fewer questions or tasks that go deeper. Teachers feel the release from planning reams of questions (often around 6 separate guided reading books) that produce reams of evidence (that needs marking) and that feel like onerous demands particularly to weaker readers. The graphic we have used to conceptualise the layers of depth in reading comprehension supports cyclic planning. Readers are regularly asked to think critically and evaluatively – not just at the end of the unit or if they have reached a level of competence.

If you are read to and you are supported to make strong connections with a text before and during your reading journey, then critical thinking and reflection becomes possible for all learners – particularly if we think collaboratively.

- This takes us to the final big shift that teachers have recognised in their practice: an improved ability to facilitate readers’ inter-thinking. When we reach the higher order reading skills of making plausible deductions, inferences, interpretations and evaluations, the direct modelling of reading strategies will eventually be found wanting. Making complex or elaborated inferences is not an algorithmic process. It involves noticing and holding multiple possibilities, and testing out their plausibility as you journey through the text and encounter – or bring – further evidence to your contingent hypothesis. Sounds too hard? In practice, we have been exploring what this looks like in year R and KS1 as much as at KS2.

Blended Reading is not a ‘model’ for teaching reading. It supports teachers to develop their principles and build provision on these:

- Teachers understand the layers in comprehension: literal, inferential and evaluative and teach all layers to all children

- The quality of texts – and linked texts – matters

- The quality of dialogic talk is key to readers adopting new ways of thinking. Dialogue supports the development of decoding skills, the monitoring of literal meaning and the building of inferences

- Teachers should use different classroom contexts and structures to their best advantage

2. How do the schools know that reading competence and confidence is improving?

The day of the ‘happy sheet’ as true evaluation of professional development is over. I care whether teachers feel interested, motivated and actually somewhat challenged at the end of an initial session together. I gathered this level of response in live interactions and via Surveymonkey and felt content that we had a good launch pad from which we could adapt practice over time.

What really matters is that a PD course ultimately affects teachers’ own confidence and competence, which in turn leads to improved outcomes for children. The schools themselves, where possible, have been tracking the impact of adapted practice on progress and attainment data. Case studies to follow soon! The data we collected in June – two terms in – was qualitative data that looked for early indicators of impact in teacher and pupil behaviours. Professor Robin Alexander explores this eloquently here. It can take time for dialogic teaching to develop confidently in live practice and affect progress as it is manifest in test results.

What follows is a summary of the indicators we captured, that have a good correlation with those used to evaluate the latest EEF dialogic teaching trial

In qualitative teacher reflections teachers felt:

- More confident to set questions and tasks that supported all learners to deeper challenge in reading

- ‘amazed’ at the level of understanding their children could develop when given structured time to inter-think

- More confident to use poetry

- Pupils were exhibiting a greater enjoyment in reading lessons – even though the texts and questions were harder.

- Creative writing tasks were being used more frequently as access to as well as assessment of reading.

- Creative writing was improving from the influence of richer texts and text-talk

In teacher to pupil exchanges, teachers noticed:

- Using richer questions and designated think/talk time led to more universal engagement with the task

- The growing confidence of previously lower attaining or less confident readers to share responses

- They relied far less on overt evaluative praise and more on authentic follow-up questions…

- They were more willing to stay with one pupil and explore reasoning ‘What led you to think…?’ ‘Could you tell us more about…’

- They were encouraging pupils to inter-think ‘Did any group have further evidence of point x?’ ‘Did any group think differently?’ ‘So far we have ideas X and Y, which do you think is most likely?’

In pupil to pupil exchanges, teachers noticed:

- Increasing self-reliance and ability to self-regulate in small group discussion

- The increasing ability of pupils to provide extended responses using more nuanced vocabulary

- Pupils beginning to build on, challenge or question each others’ responses

- The increased confidence of previously less confident readers to tackle a new and unseen text

There is – always – further to go. All delegates have focused priorities for the next steps in their own practice – or areas to take across the school. Our indicators suggest we are moving in the right direction. Increasing reports from schools on improved progress in standardised reading tests and SATs data suggest we can be confident we are working on the right things.

If you would like to join one of the Hampshire groups – or would like BR4M in your school or cluster – do get in touch.