Classifying a text part 2

or

Playing intergenerational snap

Having said in my previous blog that LTE Classification lessons have a tendency to be less emotive and more cerebral in the classroom, the exact opposite happened with my family. There was an increased sense of fun, energy and buoyancy to these sessions. Is it the Liverpudlian genes? They are probably not irrelevant. But it was also, I think, the quality of the texts. I like to think that Margaret Meek would have approved of how engaging and how troublesome they are. The other dimension was the diversity in our collective pack of snap cards (see previous blog for explanation of the metaphor).

The first is a text that its own author has shied away from classifying.

You can read Neil Gaiman’s Instructions online here. I would highly recommend that you read it. It is poignant and fun and joyous and solemn.

My family were sent the text to read together without the author’s name and asked to discuss before meeting online:

What genre of text might this be?

Answers were hugely diverse and playful: listen to the snap cards.

We thought it was a poem.

Why?

Well, the way it looks on the page

What is it about that page that is saying poem?

It’s in sort of sections and the lines don’t reach the end of the page.

And do you read something differently if its poem, say rather than prose.

I don’t know really. Maybe it doesn’t always make sense.

It reminded us of a religious tract. It is offering advice on how to live your life and treat others well. Like feeding those that are hungry. Not being jealous. Not losing hope.

We thought instructions for playing a video game, like cheats you look up online.

Why this?

Well because you get these kinds of characters in a game, like Zelda has elves and witches and stuff. And the story depends on how you react. So, like, the old woman who sits beneath the twisted oak will ask for something. If you give it to her, she will show you the way to the castle. That’s a hack.

We thought it was instructions for setting out in life, imaging life is like a fairytale and you have to manage all sorts of challenges but you come back home a wiser person. That bit about going home and your home being smaller than you remember, It’s like when you go back to your primary school after a few years at secondary.

Nobody was right or wrong and we already felt our pack of cards was richer and fuller.

This bridged us beautifully in to discussing:

Who is talking to whom and why? We have a clear second person address in the text.

After that precious family co-construction time, we had a pretty strong sense of agreement that this is someone older talking to someone younger who is about to set out on their life or quest. Some older family members imagined a wise old seer (Norwegian folk-tale snap-card), a Gandalf like character (related Tolkien snap-card) who has special powers to see into the future and to know the ways of the world. A brave younger family member (I love these moments) strongly and respectfully disagreed:

This speaker is older but it has to be another human who has trodden this same path and experienced the same challenges and knows that life is hard. That line ‘I will think no less of you.’ It’s like someone who respects this young person will make mistakes, like they did, and that’s okay. I think this has to be a real, human relationship, like a parent and a young person setting out into the world, not a wizard and a hero.

There was a stillness and silence. We were all rather stunned by the beauty of this thought.

A deeply felt and subtle snap-card was being played there. Dialogue between two mortal, fragile humans, cuts close, rings true, admits fragility. It’s just not the same as a dialogue framed by a fantasy, where magic can get you off the hook.

Instructions should be useful, right?

The lesson moves to discuss whether some instructions are more useful than others. It’s a playful way to probe classification reasoning. A text called ‘Instructions’ should be useful, shouldn’t it? That’s what we do with instructions, we read them to help us achieve something. They set up an efferent reading stance. What this question guides a group to do is to notice the diversity in the nature of instructions. They slip and slide around because the fairytale elements keep taking you in to an aesthetic stance.

I asked each family to pick the most useful and the least useful instruction. And wonderfully, there was a huge difference in choices made. Yet the differences ultimately brought us all closer. How could that happen?

Well, some families went for the instantly more global and generalisable instructions ‘Trust you heart’, ‘Do not forget your manners.’ Logically, if this is how your classification system works, then lines like ‘Ride the grey wolf (hold tightly to its fur)’ shuffle to the bottom of the pile.

Some of these are too specific, they are stuck in the fantasy story, so they’re not that useful if you step outside of it. I mean, even ‘Do not be jealous of you sister’ is a general good rule but a bit obvious.

We don’t think so

…pipes up a twelve year old voice.

We chose:

Ride the wise eagle (you shall not fall)

Ride the silver fish (you will not drown)

Ride the grey wolf (hold tightly to his fur)

Because we think it’s about taking different kinds of opportunities and trusting in adventures. So, like you need to hold tight, be careful, but adventures and risks will change you… They make you who you are.

This family went on to say that they had also chosen “if you are polite/ You may pick strawberries in December’s frost” as an important instruction.

Politeness costs nothing but it can unlock rare things… impossible things like strawberries in winter.

Another moment of wonder and stillness.

Going back to not being jealous of your sister, if we think of religious texts, sister and brother is synonymous with neighbour – like your spiritual family. I think it’s important we don’t take this literally (spoken by a not very religious kid with a great Religious Studies teacher).

Those that were playing their Psalms and Kipling’s ‘If’ snap cards of aphoristic wisdom were quite visibly redressing their thoughts (cognitive conflict, folks). This possibility to read the wolves and the witches, the strawberries and the eagles as symbolic instructions, was not just plausible, but highly seductive.

Seeking coherence is an important reading goal. As a reader of early primers, we are taught to ‘make it make sense’ – if the line doesn’t make sense, re-read it. Go back and find where the meaning broke down and fix it. The self-regulating reader is constantly monitoring whether the mental model they are creating is making sense – is fitting together. But this model is built not just from being in conversation with this text, but bringing those snap card matches into play, while you make meaning with this new, novel text. The metacognitive reader can bring those previous reading experiences to bear on their model making. What’s the same, what’s different? What fits, what’s wriggling free and being problematic?

I suspect Gaiman knows this. With Instructions, we have to hold the inconsistencies together – notice them yes – but be fascinated by them rather than fix them. How texts teach what readers learn…

At this point, I think everyone’s frame of reference had begun to loosen up. The collective classification system was a rich and diverse pack of snap cards we were all rather marvelling at, not trying to win the argument with.

And now…a picture book Snap Card!

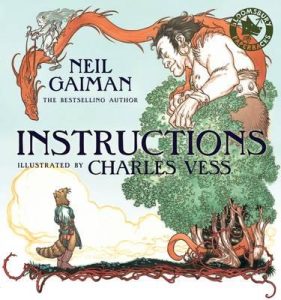

At this stage in the lesson we reveal that years after its initial incarnation, Gaiman’s text was transposed into a picture book illustrated by Charles Vess. You can watch an online version here.

Now this was a really interesting moment. How do the illustrations change the text? Everyone thought the illustrations were beautiful. They did not have a problem with the style, or the choice of the young fox protagonist. But the evaluation came quickly that they preferred to read the text on its blank sheet of A4 paper. I held up the object of the picture book that I own and our beautiful 10 year old said – ‘But that’s for children, this is for young adults.’

Everyone wanted to stay in their own, vivid and varied mental representation of the text that had certainly become something rich and strange by journeying through it together. It was unanimous.

So we moved to reflections.

Gaiman has said of his text that it was written to answer the question: What would you do if you found yourself in a fairytale.

Again – this was rejected. It was argued very clearly that this purpose was too narrow and too specific.

Now, my beautiful family in lockdown have become motivated by, if not a little addicted to bridging tasks .

Give me something to focus the mind on and puzzle over and feel proud of?

Perhaps.

The choice:

How would you illustrate Gaiman’s text and who would your protagonist be?

Or

We discussed Gaiman’s classification of Instructions as answering the question: What would you do if you found yourself in a fairytale? Relate this to a genre you know and like. What would you do if you found yourself in a dystopia, for example.

I’m including two examples. First, an illustration:

I was surprised and a little shocked by the Dodo as protagonist. I mean, he’s doomed, isn’t he? Hadn’t we read this as quite an optimistic text with a generative take on life’s adventures?

It was a great lesson in needing to hear the articulated thoughts around a student’s illustration to enter the quality of their reasoning. This teenager had assimilated that arresting view of his cousin that the protagonist needs to be mortal and brave. This is a doomed dodo – but look at the way he faces up to the instability of the worm at the heart of the tower. He was redefining our classification of the dodo.

Now an example of the second bridging task. English teachers: brace yourself.

What would you do if you found yourself in a Shakespeare comedy?

Your journey may begin in a storm , don’t worry, that means there will be a happy ending and just so you know…there will always be a happy ending, for most. Those characters that embody pure rationality, control and abstinence, will be proven wrong. Those that follow their desires and wild impulses will be rewarded, it’s not a fair world, but it is a lot of fun.

Elders often mistreat the young, but will learn the error of their ways.

Head for the countryside if you can, wisdom can be found in trees.

If you meet a young man she is probably a girl.

Servants are often cleverer than their masters and the fool is the wisest of all.

If a noble man thinks his wife is having an affair, she isn’t.

And if you lose a family member you will be reunited, but it may take a while

Get good at puns, metaphors and insults. Most of your battles will be fought with words. Clever rhetoric will get you heard and served you well.

Learn to duck, swerve and run away.

If anybody challenges you to a dual, agree, they are more scared than you are and someone will always stop it before it actually happens.

Both men and women will fall in love with you, and why wouldn’t they, you are adorable. Love is the centre of everything here; love lost, love found, love realised. Unrequited love, the love between family members, self-love and the love of being in love.

One last final tip. Learn to play the lute, playing will earn you pennies and appease the most troubled of love struck souls.

I cry every time I read this. It is so perfect. Not just because it was written by my sister.

The very same sister then replied to my request for some feedback on the Let’s Think process. I did not ask for a testimonial. I asked what they noticed about the process, what felt different to any other teaching they have experienced, what if anything had been weird or confusing, whether they had a favourite lesson so far and why.

This was her reply.

We are a loud and opinionated family, but what I am surprised by is how the sessions have been very disciplined and gracious. Every adult and every child is actively listening. Both of my sons, 12 and 14 have sat patiently listening to the views of others and are happy to express their own ideas. Both pieces of “homework” that have been set by Auntie Leah, have been done by the boys without having to be asked. The quality of the discussions we have had about the various pieces of writing, have been so great, that they boys feel brimming with their own thoughts and are desperate to express their ideas. Bye bye reluctant writers, hello confident, empowered, and engaged students with a great deal to say.

As far as I am concerned, I feel the sessions are unlocking my own creativity. A blank page is so intimidating and has never allowed me to produce anything interesting. Let’s Think sessions stimulate the mind, sharpen the nerves and senses. They make you question not only the words on the page but the words the author has decided to leave out, and why.

To explore texts in this way raises pertinent questions. With surgical precision, dialogue and descriptive passages are discussed and answers revealed, but not just one answer, multiple, possible answers. You find your “certain” views, morph and shift as your fellow delegates share their thinking with the group. You are left with a panoramic view of the extract, a really intimate and deep knowledge of its possible intentions, genres, styles, rhythms, energies, themes and sympathies… I could go on. I feel I am now a better reader than I was before. My judgement as to whether something is a quality piece of writing is keener.

I have not had a favourite session as all have been so brilliantly different. It would be too hard to choose.

Quite simply Let’s Think helps you and your children fall in love with literature.